|

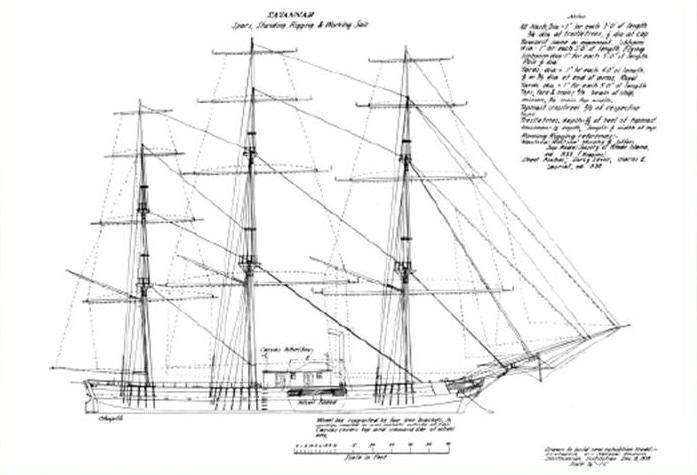

SS SAVANNAH

This page

is about the steamship Savannah. If you want a model of

the nuclear ship, please click here:

NS Savannah.

SS

Savannah was the first vessel to cross the

Atlantic Ocean partly under steam power. Savannah’s use

of steam power was so advanced for its time and so

important that the May 22 date which the ship first used

its engine in 1819 is commemorated as National

Maritime Day.

SS Savannah proved that a steamship was

capable of crossing the ocean. However, it would be

almost another 20 years before steamships began making

regular crossings of the Atlantic (and the first ships

to do so were British). Another American-owned steamship

would not cross the Atlantic Ocean until 1847.

The 98.5' long SS Savannah

was built in 1818. While she

was being built as a traditional sailing ship by the New

York shipbuilding firm of Fickett & Crockett, Captain

Moses Rogers (with the financial backing of the Savannah

Steam Ship Company), purchased the vessel. He instructed

the shipbuilders to add a

90-horsepower

auxiliary steam engine and sidewheel paddles.

The ship’s wrought-iron paddlewheels were

16 feet in diameter with eight buckets per wheel. To

reduce drag when the engine was not being used, the

paddlewheel buckets were linked by chains instead of

bars, which enabled the wheels to be folded up like fans

and stored on the ship’s deck. In addition, the

paddlewheel guards were made of canvas stretched over a

metal frame; it could also be packed away when not in

use. The process of retracting the wheels and guards

only took about 15 minutes. The SS Savannah is the only

known ship to have been fitted with retractable

paddlewheels.

Because the ship did not have enough

space to carry much fuel, the engine was intended to be

used only in calm weather, when the sails were unable to

provide a speed of at least four knots.

SS Savannah

had 32 passenger berths divided among 16 large and

comfortable staterooms. There were three fully furnished

saloons, furnished with carpets, curtains and hangings,

and decorated with mirrors. The ship’s interior was

described as more closely resembling a pleasure yacht

than a steam packet.

A short “sea-trial” of two hours was

conducted in New York Harbor to test the Savannah’s

engine on March 22, 1819. Less than one week later,

(March 28) the Savannah sailed from New York to her

operating port of Savannah, Georgia. On the morning of

March 29 the ship’s steam-powered engine was started,

but was only used for 30 minutes before being shut down

due to rough weather. The Savannah reached her namesake

port on April 6. The steam engine and paddlewheels were

used for 41.5 hours of the 207-hour voyage.

A few days after the Savannah arrived in

Savannah Harbor from New York, President Monroe visited

nearby Charleston, South Carolina, on an inspection tour

of arsenals, fortifications and public works along the

East Coast. When the Savannah’s principal owner, William

Scarbrough, heard about Monroe’s visit, he instructed

Rogers to sail to Charleston and to invite the President

to visit Savannah aboard the steamship.

On May 11, President Monroe took his

excursion on the ship. The Savannah departed under steam

for Tybee Lighthouse. Monroe dined on board the ship and

expressed his enthusiasm to Scarbrough regarding the

prospect of an American vessel inaugurating the world’s

first trans-Atlantic steamship service. In addition,

impressed by the ship’s machinery, Monroe invited

Scarbrough to sail the ship to Washington after her

trans-Atlantic crossing for an inspection by Congress.

Following President

Monroe’s departure, the Savannah’s crew, with Captain

Moses Rogers in command made final preparations for the

Atlantic crossing. The ship’s owners sought passengers

and freight for the voyage, but no one was willing to

risk lives or property on the novel vessel. This was

several years before steam-powered railroads were

founded, and steam power was considered “too

experimental and dangerous.” Therefore, the ship made

her historic voyage with its crew only.

At 5 a.m. on May 24, 1819,

the Savannah set off for Liverpool, England under both

steam and sail. During the voyage the ship was spotted

by several others with smoke billowing from her stacks

while it outran sailing ships along the route.

The schooner Contract saw

a ship on May 29 “with volumes of smoke issuing,” and

assuming it was on fire, followed it for several hours

but could not catch the Savannah. Contract’s captain

eventually concluded that it must have been a steamboat,

and thought it “a proud monument of Yankee skill and

enterprise.”

Then on June 2, the

Savannah, moving at a speed of about 10 knots, passed

the sailing ship Pluto. After being informed by Captain

Rogers that his ship was functioning “remarkably well,”

the Pluto’s crew gave the Savannah three cheers, as “the

happiest effort of mechanical genius that ever sailed

the western sea.” Savannah’s next recorded encounter

took place off the coast of Ireland on June 19. The

cutter HMS Kite made the same mistake as Contract three

weeks earlier; it chased the steamship for several hours

believing it to be on fire. Unable to catch the

Savannah, Kite fired several shots from its cannons;

causing Captain Rogers to halt the Savannah. The Kite’s

commander then asked permission to inspect the ship. The

British sailors were “much gratified” to satisfy their

curiosity about the Savannah.

By June 18 the ship had

run out of coal and wood for its boilers. The Savannah

was off Cork, Ireland, and sailed to Liverpool on wind

power alone. By June 20, the ship reached Liverpool.

Hundreds of boats sailed out of Liverpool Harbor to meet

the unusual vessel, including a British sloop-of-war.

The ship was greeted by large crowds when it anchored at

6 p.m. The voyage across the Atlantic Ocean had taken 29

days and 11 hours, of which 80 hours were under steam

(about 11% of the total time).

The Savannah stayed in Liverpool for 25

days, during which the crew scraped and repainted the

ship, tested the engine, and replenished fuel and

supplies. During the time it was in Liverpool, the

Savannah was visited by thousands of people, including

officers of the army and navy and other “persons of rank

and influence.” On July 21 the ship departed Liverpool

bound for St. Petersburg, Russia.

The Savannah reached Elsinore (now known

as Helsingor), Denmark, on August 9. Five days later, it

sailed for Stockholm, Sweden. Arriving at Stockholm on

August 22, the Savannah was visited by the Prince of

Sweden and Norway on August 28. The ship was used for an

excursion around local islands on September 1, attended

by the “American and other ambassadors, nobles and

prominent citizens.”

While the Savannah was in port at

Stockholm, the Swedish government sought to purchase the

ship, but Moses Rogers rejected the offer. On September

5, Savannah departed for Kronstadt, Russia, and arrived

there on the 9th.

The Emperor of Russia came aboard the SS

Savannah and presented Captain Rogers with a gold watch

and two iron chairs. From Kronstadt, the ship sailed on

to St. Petersburg, arriving there on September 13.

During the voyage from Liverpool to St. Petersburg, the

Savannah’s engine was used more frequently (a total of

241 hours).

The American ambassador to Russia invited

numerous prominent figures to visit the ship, and on

September 18, 21, and 23, the Savannah made several

steam-powered excursions in the waters near St.

Petersburg. Those on the ship included members of the

Russian royal family and other noblemen, as well as army

and navy officers. As in Sweden, the Russian government

tried to purchase the ship.

On September 27 and 28, the crew of the

Savannah loaded coal and stores for the return journey

to the United States. The ship was plagued by gales and

rough seas for almost its entire westward voyage. The

engine was not used until the Savannah neared the United

States. The crossing took 40 days; the ship steamed up

the Savannah River and arrived safely back at the port

of Savannah at 10 a.m., November 30, six months and

eight days after she had departed.

The Savannah only stayed

at her home port until December 3. As was promised to

President Monroe, she set sail for Washington, D.C.,

arriving there on the 16th. While the ship was docked at

Washington, a major fire swept through the city of

Savannah on January 20, 1820, severely damaging the

business district. William Scarbrough and his partners,

the owners of the Savannah, suffered financial losses in

the fire and were forced to sell the ship.

Savannah’s engine was

removed and sold for $1,600 (about $40,000 today) to the

Allaire Iron Works, which had originally built the

engine’s cylinder. It was preserved by James P. Allaire,

and was later displayed at the New York Crystal Palace

Exhibition of 1856.

After its engine was

removed, the Savannah was used as a sailing packet,

operating between New York and Savannah. However, the

Savannah ran aground along the south shore of Long

Island on November 5, 1821, and subsequently broke

apart.

The Savannah was the

subject of a 3¢ U.S. commemorative stamp that was issued

on May 22, 1944.

We build SS Savannah model the

following sizes.

24" long

$2,990

Shipping and insurance in

the contiguous USA included.

Other places: $300 flat rate.

30" long

$3,790

Shipping and insurance in

the contiguous USA included.

Other places: $400 flat rate.

40" long

$5,600

Shipping and insurance in

the contiguous USA included.

Other places: $500 flat rate.

Model is built per commission only. We require only a

small deposit (not full amount, not even half) for

materials to start

the construction $900. The

remaining balance won't be due until the model is

completed,

in several months.

Learn more about the SS

Savannah here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Savannah

|